Historians, Data Analysis, and User Experience Research

Exploring the similarities between historians and data analysts, and considering what historian might bring to UXR

As someone trained as a historian, I always assumed that there was some distinct methodology that set historians apart from other types of researchers. Surely, there were fundamental differences between how historians planned, researched, and executed their research and how, let’s say data analysts, approached theirs. Historians at their core are concerned about change and continuity: in a world that is defined by the interplay of these two forces, they are often concerned with understanding the “why” of the present through the lens of the past. Typically, historians are trained to identify and focus on utilizing text-based or other types of qualitative sources to tell these stories (though more about that below). When I first started exploring data analysis, and its stereotypical focus on quantitative analysis, statistics, and specialized knowledge in tools like SQL (Structured [English] Query Language, pronounced sequel), the programming language R, and Tableau, I didn’t see anything similar to what I do as a historian.

Contrary to popular belief, the potential sources of a historian are as broad as their skillsets can handle. While qualitative analyses of governmental reports, personal diaries and letters, and other common text-based sources of life in the past are our hallmark, the written (and spoken) word was never the exclusive basis of our methodology. Most recently, the use of large data sets by environmental historians to understand the long-term impacts of environmental changes and human-environment interactions have revolutionized the way we approach issues like climate change. On the micro-level, quantitative data also helps historians who are interested in the quietest historical actors. Fore example, to understand the life of a single Japanese woman in the 19th century whose name is the only historical source we have left of her, historians can piece together census records, labor statistics, and economic data to provide the context in which she lived and glean insights into what her life might have been like.

It goes without saying that historians have a particular mondai ishiki (the Japanese phrase for a way of looking at things, if you will) about their research. But recently I have been interested in how I could apply my historical training outside the academy. Thanks to some kind suggestions from folks I have met along the way, I began thinking seriously about User Experience Research (UXR) and the types of data analysis that drive this field. And, as my parents remind me, being a professional student for the last three decades has predisposed me to look for new information and skills in educational materials. So, I started Google’s “Google Data Analytics” course on Coursera. Color me surprised when I realized that the foundational methodology for data analysts and historians largely overlaps.

Google lays out the methodology of a data analyst as such: Ask-Prepare-Process-Analyze-Share-Act. To briefly summarize, data analysts start by defining a problem (or being handed a business problem or question) and deciding what type of data they think they’ll need to answer it. Then, they collect that data, clean the data, decide what parts are useful, or what parts are already tweaking their hypothesis, and analyze the data more fully. Finally, they compile their analysis into sharable reports with clear takeaways and move to act on what they found. Historians, on the other hand, define a problem and decide what type of sources they think they’ll need to answer it, collect those sources, evaluate in broad strokes which sources are most useful or which sources shift how they were thinking about the problem, and further analyze these sources. They take this analysis write about what they’ve found (perhaps in a dissertation?) and present it to other historians. If you replace sources with data, you can see where I’m going here. Historians obviously have their own epistemological and methodological eccentricities (evidenced by the silliness of this sentence) but their analytical skills are also translatable, and their core competencies in technical thinking deeply similar to data analysts. It just takes a little SQL, R, and some knowledge about statistics to bridge the gap.

Let’s put this idea that historians have more in common with data analysts than not into practice with an example from UXR: using telemetry data from video game players to better understand how players are engaging with a game. In the context of video games, telemetry is a data collection method by which data is silently collected from the game while players are playing, and provides insights into player behavior, in-game actions, system performance, and other types of player engagement. Game developers then use this data to further optimize their games. An additional popular use of this data is for game studios and developers to share insights from this data with players to help them feel more immersed in the community of individuals playing the game.

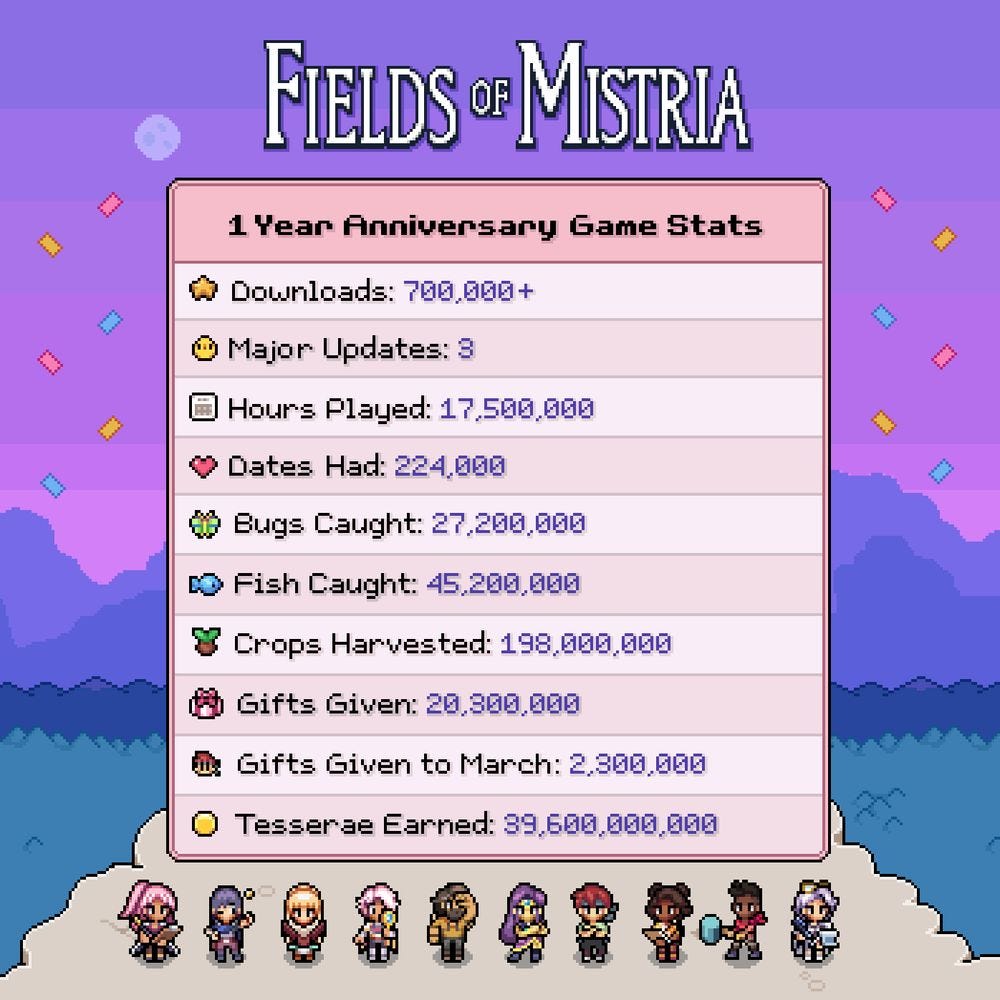

Here’s an example from a game that I’ve been playing for the last year and a half in early access (which is a fancy way of saying they let a limited amount of players play the game while they’re still finishing it):

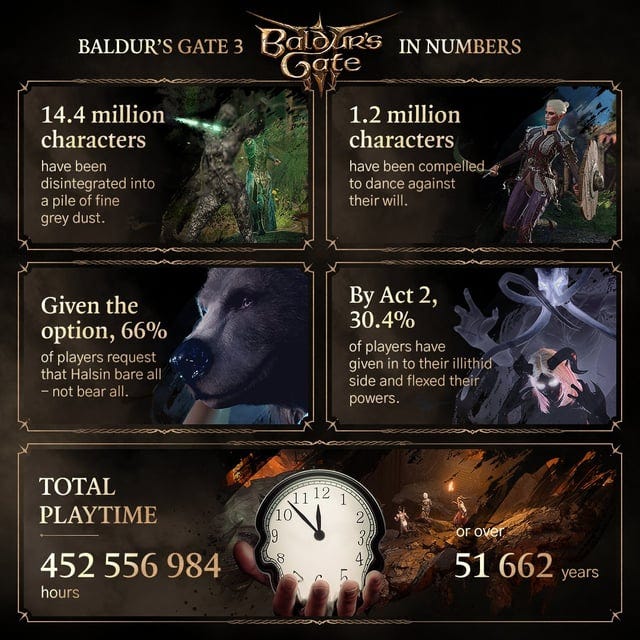

For my non-cozy gamers, here is a link to a Reddit post about Baldur’s Gate 3 with similar telemetry data as community engagement and marketing promotion. For example, this is just one piece:

Personally, I find both the internal, developer-specific needs, as well as the utility for community engagement, to be absolutely fascinating and positive uses for data. It is so fun to read about how other players are playing the game, especially what obscure and wacky things players have figured out that I had never discovered or even imagined. I, personally, was never disintegrated into a pile of fine grey dust, but that likely has more to do with my fixation on Act 1 than anything else.

What I as a historian find so interesting about the possibilities of telemetry data is how studios can use that information to better understand player behavior over time in order to shape it. For example, consider a live service game like Genshin Impact, which implements new content for users every four to eight weeks. In a live service game, you don’t just pick up a copy at the store and play through from start to finish. Live service games have a specific gameplay core that is supplemented by both time-gated events and incremental expansions, whether that be in the size of the playable map, or in the number of characters, or even in new in-game activities that become permanent. Using telemetry data, in addition to conducting player surveys and in-depth interviews (IDI) with individual players, studios can understand how players are playing and what they spend their time on, what they like or dislike, among other things. These types of insights help developers understand which aspects of their game are popular, or largely ignored, or even bugged. Because these games are ongoing (Genshin Impact is now five years old), the telemetry data now forms a historical record for understanding player behavior over time.

Let’s think up an example of how this works. Say a game developer or studio (in this case Genshin Impact) wants to launch a new (monetized) feature into the game. They know from their player surveys, IDIs, and telemetry data from the last few years that players consistently spend a lot of time exploring the world and interacting with NPCs. To this point, some of the NPC dialog has included small in-game rewards, like scavengable items, nuggets of story lore, or other desirable outcomes that can only be uncovered after interacting with the NPC. If the player doesn’t engage, they’ll never know that these rewards exist, but the rewards are generally not substantial enough to make this a pain point for players. To add value to this existing behavior, the Genshin Impact’s developers began adding in character-specific dialog choices.

Genshin Impact is a “gacha game,” or a game the revolves around using in-game currency or real money to acquire playable characters, though the game itself is free to download and play. Players can collect individual characters who make up four-character teams that constitute the game’s core mechanic. These characters can be acquired both through in game resource accumulation (Free to Play or F2P), or by purchasing in-game currency to try and acquire these characters through a roulette-like system. While the majority of players are F2P, the use of real money increases the number of times a player can “wish” for a new player.

Tying (limited) character-specific dialog choices into the existing system of exploration and NPC interactions connects a common player behavior more closely to the game’s key monetization system of acquiring new characters. It adds additional value (in the form of expanded functionality) to an existing feature that rewards players for using new characters. The rewards aren’t large enough to make it feel unfair to F2P players who might accumulate new characters more slowly. At the same time, the few functionality subtly validates the decision of players who do acquire the new characters and who are surprised to discover the new dialog options that the character unlocked, pushing them to explore further and with more characters.

Perhaps one does not have to be a historian to understand the logic behind releasing a feature like the one mentioned above. But the example of utilizing telemetry data with a historian’s attention to change and continuity over time and their commitment to fully framing the context of this dynamic can make them valuable members of UXR teams.